Seoul summer lunchtime questions and BRICS

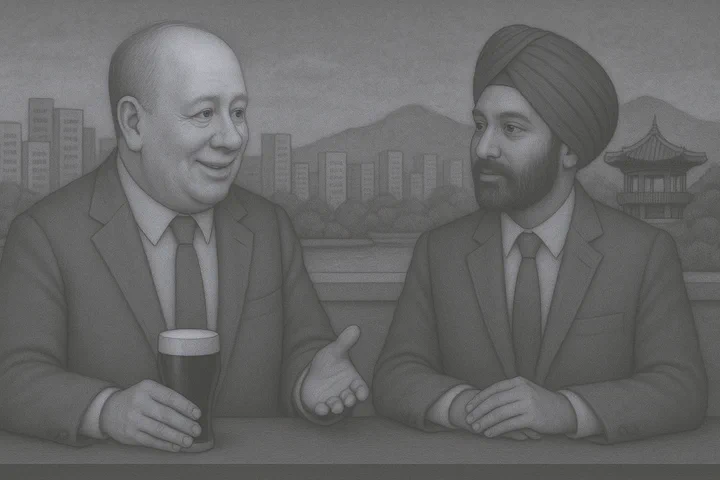

Lowly schmuck academics like yours truly, unfortunate enough to still be in Seoul at summertime are often invited by public officials to standard fare lunchtime sessions of questioning and soul-searching. Sometimes it’s to subtly solicit you to write more on a subject and sometimes it’s to subtly reprimand you for writing on another subject. But sometimes you leave the Improper Solicitation and Graft Act adhering, KRW50,000 luncheon, wondering what was that all about?

Then, one day you’re speaking to a more senior academic colleague. He or she took in a more exquisite dinner and a drinking session with senior political figures - the kind of meals that escape Improper Solicitation and Graft Act adhering, KRW50,000 limits, because of the personal, longstanding, relationships between old friends, who solidly argue that the cost of the exquisite meal (and the subsequent whisky and entertainment) didn’t need to conform, and maybe even didn’t even happen when it comes down to it. That colleague tells you something that strikes a chord. The conversation of the cheap meal and that of the exquisite meal shared one subject in common.

This may or may not have happened in the recent past, and the common subject may or may not have been the question of South Korea and BRICS!

The BRICS??? The idea of South Korea joining BRICS is absurd! South Korea is a U.S. ally and a beneficiary of the U.S.-led liberal-international order. Why would it join an organization built to grumble and arguably even break down the global order?

Yet, deeper engagement with the BRICS framework—or its expanded form, BRICS+ is now a question being asked in South Korea.

These discussions are driven not just by ideology and opportunism but also by a broader concern: the global order in which South Korea has long anchored its foreign and economic policy is fragmenting, and that contingency planning is now prudent statecraft.

The obvious factor driving this conversation is the erosion of predictability in South Korea’s alliance with the United States. The Trump administration’s transactional approach to alliances, particularly its demands for steep increases in defense cost-sharing and threats of troop withdrawals, has forced Seoul to confront the possibility of a future in which U.S. security guarantees are less reliable and more conditional. From the first Trump Admin, through Biden, and on to Trump 2, an underlying concern of many is that the U.S. commitment to its Asian alliances appears increasingly dependent on domestic political cycles, not strategic consensus.

This uncertainty has prompted a quiet exploration of alternative or complementary strategic relationships. NATO-like alliances on the table seem impossible, but broader patterns of alignment—particularly with Global South coalitions such as BRICS—have begun to appear in internal assessments as worth evaluating. The logic is not one of replacement, but of diversification: how can South Korea strengthen its resilience in a world no longer defined by unipolarity?

South Korea’s economic diversification strategy already aligns, in part, with BRICS+ dynamics. Korean conglomerates have significantly expanded investment and trade ties with India, Indonesia, the UAE, and Brazil—countries that now constitute either core or adjacent members of BRICS+. Meanwhile, Seoul’s outreach to Africa and the Middle East has grown in scope and ambition, underpinned by development cooperation, infrastructure finance, and digital technology partnerships.

The idea is not to signal alignment with anti-Western agendas, but to recognize that BRICS+ is emerging as a parallel, if still incoherent, architecture of global governance.

There is also a growing recognition that as the Global South asserts more influence in multilateral institutions—both in numbers and in agenda-setting—South Korea’s long-standing aspiration to be a “bridge” or “middle power” between developed and developing nations can play a role. In forums where BRICS+ is becoming the de facto organizing framework for non-Western diplomacy, Korea risks being structurally sidelined if it remains wholly outside those dialogues.

Any formal engagement with BRICS remains constrained by structural and political realities. Foremost is the question of strategic alignment. As a U.S. treaty ally hosting significant American military assets, South Korea’s entry into a bloc that includes Russia, China, and Iran would likely be viewed in Washington—and Tokyo—as a strategic breach, even if cast as economic pragmatism.

Domestic political divisions also limit maneuverability. Any government exploring closer ties with BRICS would face strong scrutiny from conservatives and segments of the national security establishment wary of weakening alliance cohesion. Even technical cooperation with BRICS institutions would require careful framing to avoid backlash.

Further, the BRICS bloc itself remains internally fragmented. China’s outsized influence, the absence of clear governance rules, and divergent member interests make it a difficult forum for middle powers seeking institutional predictability. South Korea’s policymakers remain justifiably skeptical of frameworks in which power asymmetries are not addressed through robust norms.

But South Korea is not seeking BRICS membership. There are no formal negotiations, no imminent policy shifts, and no clear roadmap that would make accession likely under current conditions. It is merely thinking creatively—and this a change.

The fact that the question is now being asked—by officials, business leaders, and scholars alike—reflects a deeper structural trend: the world is entering a phase of multipolar fluidity, and countries like South Korea are beginning to think beyond inherited alignments. The value of the BRICS question is not in whether Seoul joins the group, but in what the question itself reveals about Korea’s evolving strategic posture.

It suggests that hedging, once a taboo subject in alliance politics, is becoming normalized—even necessary. And it underscores that in the quiet corners of diplomacy and policymaking, the architecture of Korea’s next foreign policy era is already being debated.