Manufacturing the next generation of North Korea watchers

At every conference on North Korea, you’ll see them—the go-getters. They’re bright-eyed students and early-career scholars who tick all the right boxes: educated at respectable institutions, interned at the right think-tanks, cycled through the obligatory “next-generation” fellowships, and now orbiting policy circles as youthful ambassadors of conventional wisdom. They are photogenic, energetic, multilingual, and… above all, predictable.

The North Korea watcher “Go Getter” is not dangerous because they are reckless, radical, or misinformed. Quite the opposite. They are dangerous because they are so thoroughly domesticated by the machinery of influence production that they no longer question it. Their very success depends on a well-rehearsed performance of policy orthodoxy—one that rewards shallow novelty wrapped in the right demographic packaging.

It’s a highly refined process of indoctrination, repeated again and again.

It starts at university. The “Go Getter” gravitates toward international studies or East Asian security. They join the Korea-focused student society, attend panels hosted by regional embassies, and take selfies at consulate receptions. But the real turning point is the internship. Placement at a U.S.-based or U.S thinktank sponsored program launches them into the network. This internship is unpaid, of course, but rich in networking opportunities and exposure to spreadsheets, footnotes, and boilerplate policy memos.

From there, the “Go Getter” enters the policy-academic circuit. They apply for “rising scholar” programs, most of which are thinly veiled grooming platforms for public diplomacy efforts. These programs are less about scholarly insight and more about grooming participants into manageable, presentable faces of youth opinion. They glide through postgraduate study to Masters or PhD level, and by the time they hit 26, they’ve already spoken on more panels than they’ve read original North Korean documents.

Every “Go Getter” quickly learns the importance of crafting a personal brand. It must signal energy, empathy, and global citizenship. They tweet threads with emojis, offer takes that never offend donors, and write op-eds with titles like “Why Dialogue Still Matters” or “North Korea’s Youth Deserve Hope Too.”

But despite the glossy surface, the content is numbingly familiar. They recycle the standard talking points: deterrence is good, dialogue is better, sanctions must be smart, human rights are essential, and regional cooperation is crucial. The words are rearranged endlessly, but the substance rarely deviates from the script. They never question the U.S. or its role in the region.

This is not because they lack creativity or intelligence. It’s because they’ve been taught—explicitly or through osmosis—that influence is built on being agreeable, professional, and easily quoted. So they learn to be quotable, not thoughtful. Digestible, not critical. They become, in effect, influencers of the status quo.

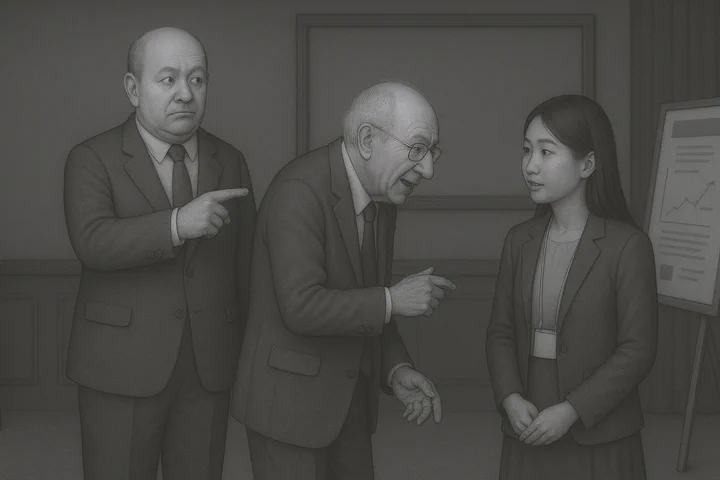

Many “Go Getters” find additional leverage through identity. Institutions love to showcase “diverse voices”—especially if those voices echo the dominant line. We all know that U.S. thinktanks were until recently, some of the last bastions of grumpy, old white men on the out and out after a life of policy work. Boomers rarely want to give up their own benefits, but love to pull the rug out from those below them, so equity and diversity started with graduate and next-generation programs.

A Korean-American “Go Getter” who speaks of peace while backing trilateral military cooperation fits beautifully into this dynamic. So does a young woman of color discussing “empathy” in North Korean policy while avoiding any mention of failed humanitarian interventions.

These figures are deployed at conferences, symposia, and roundtables as evidence that the field is changing. But the field is not changing. It’s just learning how to better market the same stale framework in a more photogenic package. The “Go Getter” becomes a token of reform, all while reinforcing the very stagnation they believe they are escaping.

The career arc of the “Go Getter” reaches its apex with the publication of a report—typically co-authored—on the “next steps” for U.S. policy on North Korea. The report will include all the right phrases: “comprehensive strategy,” “stakeholder engagement,” “confidence-building measures,” and “non-proliferation goals.” It will not include a serious rethinking of the logic of sanctions, the political motivations behind regime resilience, or the failures of past summits. Instead, it will read like a group project turned in late to a professor who’s already assigned everyone a B+.

Meanwhile, their Twitter bios will now include “published in Foreign Affairs,” “commentary on CNN,” and “speaker at Brookings,” as if these endorsements validate the work rather than the ecosystem that produced it.

The problem isn’t just the individuals. It’s the system that rewards performance over insight. The “Go Getter” model creates a generation of North Korea experts who are more responsive to institutional needs than geopolitical realities. Their allegiance is to think tanks and institutes, not fieldwork; to donors, not dissenters.

And the consequences are real. When North Korea policy is shaped by echo chambers of trained consensus, it leaves no room for disruptive ideas, for genuine re-evaluation of assumptions, or for voices that don’t fit the “emerging expert” mold.

We get more panels and less substance. More retweets and less reflection. The illusion of fresh thinking without any real challenge to the stale paradigms.

Many “Go Getters” burn out by their early 30s. Having chased credibility through fellowships and fast takes, they either pivot to more lucrative fields—consulting, government, or tech—or settle into the policy-commentary middle class. A few become gatekeepers themselves, mentoring the next wave of Go Getters with the same advice they once received: publish often, stay on message, and never challenge the institutions that feed you.

And so the cycle continues. The watchful gaze on North Korea remains, but the lens never widens. It’s not analysis—it’s choreography.

The North Korea watcher “Go Getter” is not the future of the field. They are its symptom. What’s needed is less hustle and more heresy—voices willing to break the pattern, not replicate it with a better LinkedIn photo. But that kind of watcher rarely gets the fellowship. Or the panel slot. Or the funding.

They’re too busy actually watching and thinking of solutions.