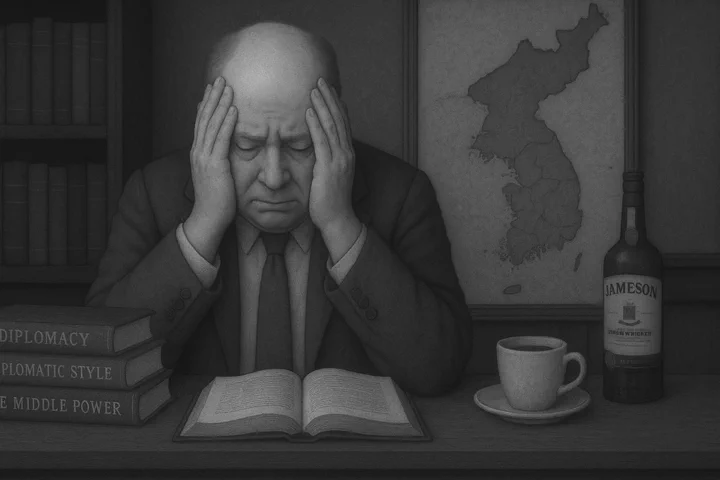

Iran strike raises concerns in South Korea

So, the U.S. joined Israel with strikes on three Iranian nuclear sites—Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. There was no Security Council resolution, no ultimatum, no final warning. There were no reports of an imminent and immediate Iranian threat, no visual evidence of noncompliance with international agreements. In fact, Iran had continued to abide by the core obligations of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and remained under partial inspection by the IAEA.

There were a few bizarre Trump tweets conflating Israel with the US; implied threats on the location of the Iranian leader; and an ambiguous presser with Trump saying “we’ll see” and something equally blase about how Iran had “two weeks”.

U.S. foreign policy and its lack of predictability now looks dangerous for South Korea—and that’s without considering the second and third-order effects.

The greatest concern for South Korea is the strike’s immediate impact on the normative foundation of international order. With this act, the United States—long the self-declared steward of global rules—formally abandoned any pretense of playing by them. This was not preemption. It was not protection. It was not even politics cloaked in legality. It was raw, unmediated power.

For decades, the liberal international order has functioned not simply as a web of treaties or institutions, but as a system of expectations: that powerful countries would constrain their behavior with reference to international norms, and that weaker states could navigate global affairs with some assurance that outcomes were not determined purely by might.

The U.S. strike on Iran demolishes that premise. It was not just highly questionable under international law; it was casually so, undertaken with no clear justification beyond “we can.”

There was no moral rationale on offer, not even the strained logic of humanitarian intervention or helping Iranians to choose their own leader. The justification offered was incredibly opaque and illogically strategic—centering vaguely on deterrence and the elimination of potential threats. But Iran had not attacked, and even by Washington’s own standards, had not crossed any red lines. There was no triggering event, no escalation, no provocation except Iran’s refusal to renegotiate under threat! The up to “two weeks” Trump spoke of passed in eerie silence—and lasted three days!

This was a move not designed to punish illegal behavior, but to punish defiance. The U.S. struck because Iran refused to play ball. That the sites hit were non-operational or undergoing inspection is, in this light, irrelevant. The purpose was never arms control. It was to remind the world who rules - but misses the fact that the U.S. will now be occupied in the Middle East and neglect Asia.

For U.S. allies, the implications are staggering. Not because they fear the same fate, but because the underlying principle of strategic reliability has evaporated. In theory, the U.S.-led order provided predictability, balance, and a shared sense of direction. But today, the United States acts on impulse, not deliberation. It issues threats in vague terms, waits a few days, and then acts without consulting even its closest partners.

Nowhere is this more consequential than in South Korea. For decades, Seoul has built its security architecture around the assumption of American reliability. The U.S.-ROK alliance has rested not just on shared interests but on shared rules and habits of coordination. But what happens when that predictability disappears?

South Korea must now contend with the possibility that alliance politics are being conducted on a whim. Trump’s strike on Iran was not preceded by coalition-building or burden-sharing. It was a decision made in isolation, reflecting domestic political incentives more than any calculable security logic.

For South Korea, this introduces a dangerous uncertainty in any North Korea crisis.

If North Korea escalates tensions, will Washington respond proportionately—or will it react impulsively, using South Korean territory or bases without adequate consultation?

Worse, would a provocation elsewhere suddenly draw U.S. resources away from the Korean Peninsula? This erosion of reliability is not abstract. It forces a recalibration. If the United States cannot be counted on to act rationally, legally, or transparently, then it ceases to be a dependable strategic partner.

South Korea, already balancing its relations with China, may now be pushed further into the logic of hedging—not out of preference, but necessity. A partner that ignores international law, acts unilaterally, and behaves with escalating unpredictability is not simply burdensome—it is dangerous.

The U.S. decision to strike Iran without warning, justification, or legal grounding also invites global instability. It sets a precedent that powerful states can act without constraint, that legal compliance offers no shield, and that diplomacy is subordinate to force.

Worst of all for every smaller state, the strike empowers actors—Russia, China, India—to model their behavior on this new norm: strike first, explain later, if at all.

There is no liberal international order now. There is only a loose framework of still-functioning institutions slowly being hollowed out from the top down. The U.N. was not consulted. NATO was not convened. The IAEA was not referenced. Instead, the U.S. acted like an empire, not a republic.

It may take years before historians agree on when the liberal order truly ended. Some may point to the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Others may cite Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Accord or the U.N. Human Rights Council. But the June 2025 attack on Iran will stand as the moment the U.S. dropped even the language of legality, morality, or multilateralism. It did not just violate the rules. It declared them irrelevant.

And for allies like South Korea, that declaration is not only sobering—it is clarifying. The days of assuming strategic alignment and democratic solidarity are over. What remains is risk calculation. America is now a variable, not a constant. Less reward, more risk. Welcome to the post-order world South Korea.